Two million years ago southern Africa was inhabited by Australopithecus sediba and Paranthropus robustus. Now the discovery of a juvenile Homo erectus skull at Drimolen Cave has revealed a third species present in the area at the same time, and one much more closely connected to ourselves. Moreover, the find is the oldest Homo erectus fossil we have found, shifting the debate about where this immensely successful species evolved.

Homo erectus was the first species we know of whose body shape resembled our own, with long legs and shorter arms, indicating full adaptation to life on the ground. This helped them span much of the world, from Africa to east and south-east Asia, something unprecedented for our near relatives. They also appear to have been responsible for the first hand axes, and survived for almost 2 million years, something we may struggle to emulate.

Such a wide dispersal inevitably raises questions about where H. erectus evolved. The first finds were in Java and China, and La Trobe University PhD student Jesse Martin told IFLScience some speculation has centered on the Caucasus Mountains. However, recently East Africa, where so many other early humans appeared, has been the focus.

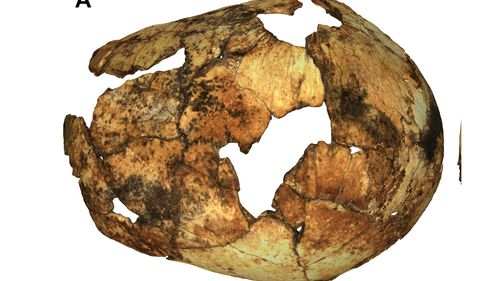

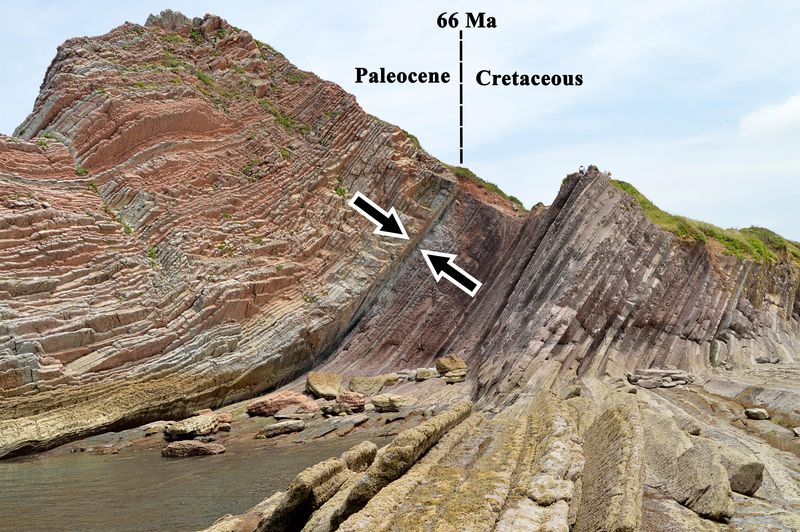

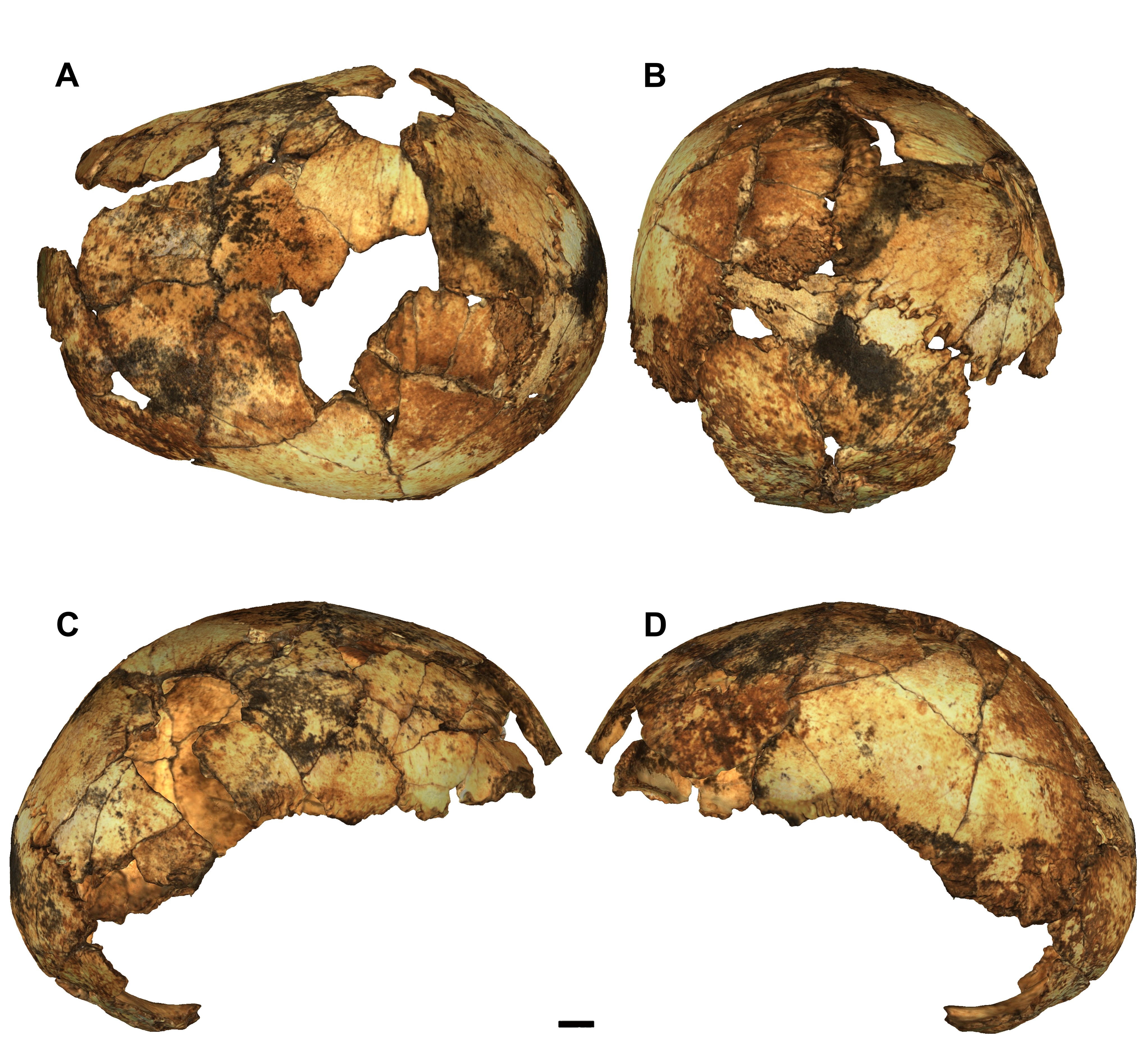

Martin has changed all that by identifying a 1.95-2.04-million-year-old skull as being from a Homo erectus child. Although it is the earliest H. erectus fossil we have, and far from fully grown, the size of the skull suggests a brain capacity too large for an Australopithecus child. Using a model based on growth rates for humans and chimpanzees Martin and co-authors estimate in Science the unfortunate individual was just 2-3 years old when they died.

Martin told IFLScience that had the owner survived, its brain would have been at least within the normal range for more recent members of its species.

Drimolen lies just north of a series of outcrops near Johannesburg known as the Cradle of Humankind for the abundant human fossils found there. Nevertheless, Martin told IFLScience, most Drimolen primate bones are from baboons. When part of fossil DNH 134 was spotted sticking out of some well-dated rock it was thought to be just dismissed as yet another baboon skull. Eventually, Martin, then an undergraduate student, was assigned to, in his words: “Spend weeks in a dark room with nail polish remover and a straw, getting out the sediment without touching the fossil.” Martin ironically calls the task “glamorous” having once almost chocked on a rat vertebrate.

Slowly excitement built, as Martin started to realize the skull was actually human. By the time he spoke to someone more senior he had a suspicion it was actually H. erectus, preceding the oldest find by 100,000-200,000 years.

The discovery leaves open how H. erectus interacted with Paranthropus and Australopithecus. “Paranthropus had enormous molars, 2-3 times the size of ours, and massive muscles attached to their jaw,” Martin said. “They clearly evolved to process hard foods like roots and seeds.” Although the jaw is missing from the 150 pieces Martin put together to reconstruct the skull, he said, “H. erectus instead had relatively large canines and incisors, possibly indicating they ate meat occasionally. A. Sediba's morphology indicates it pursued a very generalized strategy, probably a foot in both camps.”

Martin added that without DNA evidence it will be very difficult to determine if the three species could interbreed. “It would have been thought preposterous, but since we found out about mating with Neanderthals it can't be ruled out.”

Martin's supervisor Professor Andy Herries said in an emailed statement the discovery makes it unlikely that A. Sediba was H. erectus' direct ancestor, as many have previously thought, deepening the mystery about that major aspect of our evolution.